New DCPS report cards should be easier for parents to understand, but they may overwhelm parents with information while omitting suggestions that could be helpful.

This week,

DCPS is rolling out a new report card format based on feedback from parents and teachers.

There’s one version for middle and high school students, which explains the various kinds of GPA, records the community service hours the student needs, and alerts parents to any courses the student is failing.

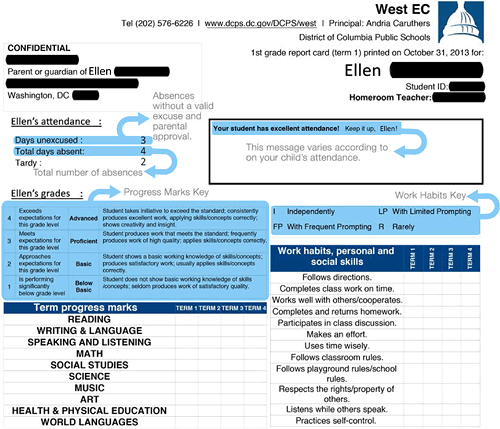

The elementary school version has a cover page with an overall snapshot of the student’s progress, including attendance, marks for each subject, feedback related to classroom behavioral expectations, and comments from the teacher. The next two pages relay more specific information regarding student progress within each subject area and standardized test scores. The final page has a list of suggested book titles for parents to read with their children based on reading level.

Report cards have grown

The four-page report card is a far cry from the single sheet of paper I brought home as a student in the 1990s. That was a bare-bones description of my academic progress, as described by letter grades. There was a small section for information about my behavior with such categories as “works without disturbing others” (which I imagine was sometimes marked “needs improvement”), and a handwritten sentence or two from the teacher.

By 2006, when I began teaching 5th grade in DCPS, a teacher was expected to prepare an extensive document for each student based on the standards for each subject. The wording of each component was highly academic.

A DCPS press release gives an example of the old report card language: “By the end of the year, reads and comprehends literature and informational texts in the grades 4-5 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.”

As a newly minted teacher, I understood the meaning of educational buzzwords like “text complexity band” and “scaffolding,” but I doubt the same could be said of my students’ parents, or even some of my older colleagues. I put in hours of work completing report cards, yet parents were still asking me how their children were doing in class. Clearly, this method of parent-teacher communication left something to be desired.

The

new report card seeks to bridge this communication gap through several key changes. One is that the language promises to be simpler. According to the DCPS press release, the “new” version of the language quoted above will be: “Reads and understands literature and informational texts on grade level.”

Too much information?

Parents will probably focus much of their attention on the cover page, which summarizes the highlights. The second and third pages contain a lot of information that could be helpful to parents, but they’re also potentially overwhelming. In the first-grade report card that DCPS has posted as an example, there are twenty standards listed for reading and language arts alone.

While I appreciate the thought behind the list of books on the final page, it seems impractical. The same list is likely being given to students across the District, which means that it will be hard for parents to track down these specific titles at a library.

Also, in my experience, parents feel less comfortable helping their children with mathematics than reading. But the suggestions don’t include any math resources. In our technologically focused world, a list of websites or even apps that focus on reading and math might be more useful, at least for parents with access to computers.

Still, while there’s room for improvement, the new DCPS elementary report card is a step in the right direction.

Update: DCPS is inviting parents to comment on the new report cards here.

I’m an all-around believer in the public school system. Yet this fall I opted to send my son to a private school in Maryland. We failed at the charter school lottery, and our neighborhood school isn’t a good fit. And ultimately, my decision was made easier by the fact that next year, we can think it all over again.

I was always a public school kid. From kindergarten through high school, then right on through college, it was public school for me. Growing up in suburban Chicago, I had a first-rate education within walking distance of my house. And I’m a former DCPS and charter school teacher.

I believe that every child is entitled to an excellent, free education, and it is only when parents invest in their local schools that this can be a reality. Why, then, does my 3-year-old son, born and bred in Washington, attend a Catholic preschool in Hyattsville? Well, let me tell you:

1. He didn’t get in. As a former DC charter school teacher, I was not intimidated by the charter application process. I looked at all the possibilities, ruled out the ones that were too far away, and filled out application after application. And guess what? He did not get into a single school that I applied to. At Latin American Montessori Bilingual (LAMB), my top choice, his lottery number was somewhere north of 700.

2. I was looking for added value. I am a teacher-turned-stay-at-home-mom. I have a one-year-old in addition to my son, so I knew that I wasn’t going back to work this year. I like being home with my children. So, if I was going to send my boy off for a large part of every day, I wanted to know that he was getting something that he couldn’t get at home. A dual-language program would have met this criterion, or perhaps one with expeditionary learning. The school that our family opted for has a traditional Montessori program for 3- to 6-year-olds, which is well-suited to my son’s personality.

3. Our neighborhood school was not a good fit. We live in Eckington, and our neighborhood school, Langley Education Campus, can be charitably described as “up and coming.” There is a cohort of involved parents, some dedicated teachers, and a new principal. In a few years, I think it is going to be great. Even now, it is a safe, learning-filled place. For parents who need to send their kids to school for 7 hours a day, it is no doubt better (and much more affordable) than daycare. But my son just turned 3 in September, and to send him off all day, every day, seemed like too much. His preschool is a half-day program (with a full-day option), which gives us lots of time in the afternoons to pursue his other interests.

4. It’s a one-year decision. There were some agonizing moments this summer as I contemplated my son’s school destination. After all, what more important role do we have as parents than helping our children find their path in life, beginning with school? When I took a step back, though, I saw that I wasn’t determining his future with this one decision. Our family may stay in DC, or we may not. Next year, I may feel like our neighborhood school is a better fit. Or, by some miracle, we may win that coveted spot at LAMB. In the end, our family chose what we thought was best, for now. Next year? We’ll wade in those waters when we get there.

Other DC families, what has been your school choice experience? GGE would love to hear about it, so please share your story in the comments below. Or click on “Contribute” at the top right-hand side of this page for information about submitting a guest post.

Top image: Photo by the author.

Wearing a uniform was once the mark of private school attendance. Now public and charter school students are suiting up as well. But do the uniforms have to be so expensive?

About 3 out of 4 DCPS schools now require uniforms, according to a DCPS spokesperson. Although there are currently no statistics available for charter schools, it’s clear that many if not most of them have their students wearing uniforms as well.

The benefits of such policies are well-documented. A study of urban high schools in Ohio found that while uniforms didn’t directly affect academic performance, they had a positive impact on attendance, graduation rates, and rates of suspension. Long Beach, California reported a dramatic increase in school safety after implementing a uniform policy in all K-8 schools. As a teacher, I also observed some positive effects of having students wear uniforms, such as fewer distractions in the classroom and a shift in student focus away from physical appearance.

Now, as a parent, I’m seeing the issue from a different angle. The problem for parents comes down to the cost of uniforms, and in some cases, the effort of procuring them. My son’s private school requires students to purchase polo shirts with the school logo at a cost of $18.50 apiece, with an additional charge of $9.50 for shipping. A friend had a similar experience when her children attended Community Academy, a public charter school. Shirts plus pants plus shoes add up quickly, so I was not surprised to find that the average cost of school uniforms for parents is $249.

The DCPS schools requiring uniforms that I have encountered generally have a more flexible policy than my son’s school or Community Academy. They dictate a specific color or two of polo shirt for students to wear, along with khaki bottoms.

This approach allows parents to shop around for affordable options. And according to DCPS regulations, students who do not wear a uniform because they can’t afford one are not subject to disciplinary action. DCPS schools are also required to establish a mechanism for providing aid to students who cannot afford the uniform.

Some DC charter schools, like KIPP DC and Mundo Verde, have an even easier, more affordable uniform strategy. While these charters expect parents to independently provide pants, shorts, or skirts for their children, the schools contract for custom t-shirts that parents can purchase directly from the school at a low cost. KIPP gives its students one shirt as a gift at orientation. By providing the shirts directly, schools are also able to assist low-income families without extra steps like vouchers or reimbursement.

Parents, have you had any positive or negative school uniform experiences, either in DCPS or at a charter school? Leave us a comment and tell us about them.

Top image: Photo by the author.